It seems like half of the battle in statistics is identifying an important/unsolved problem. In math, this is easy, they have a list. So why is it harder for statistics? Since I have to think up projects to work on for my research group, for classes I teach, and for exams we give, I have spent some time thinking about ways that research problems in statistics arise.

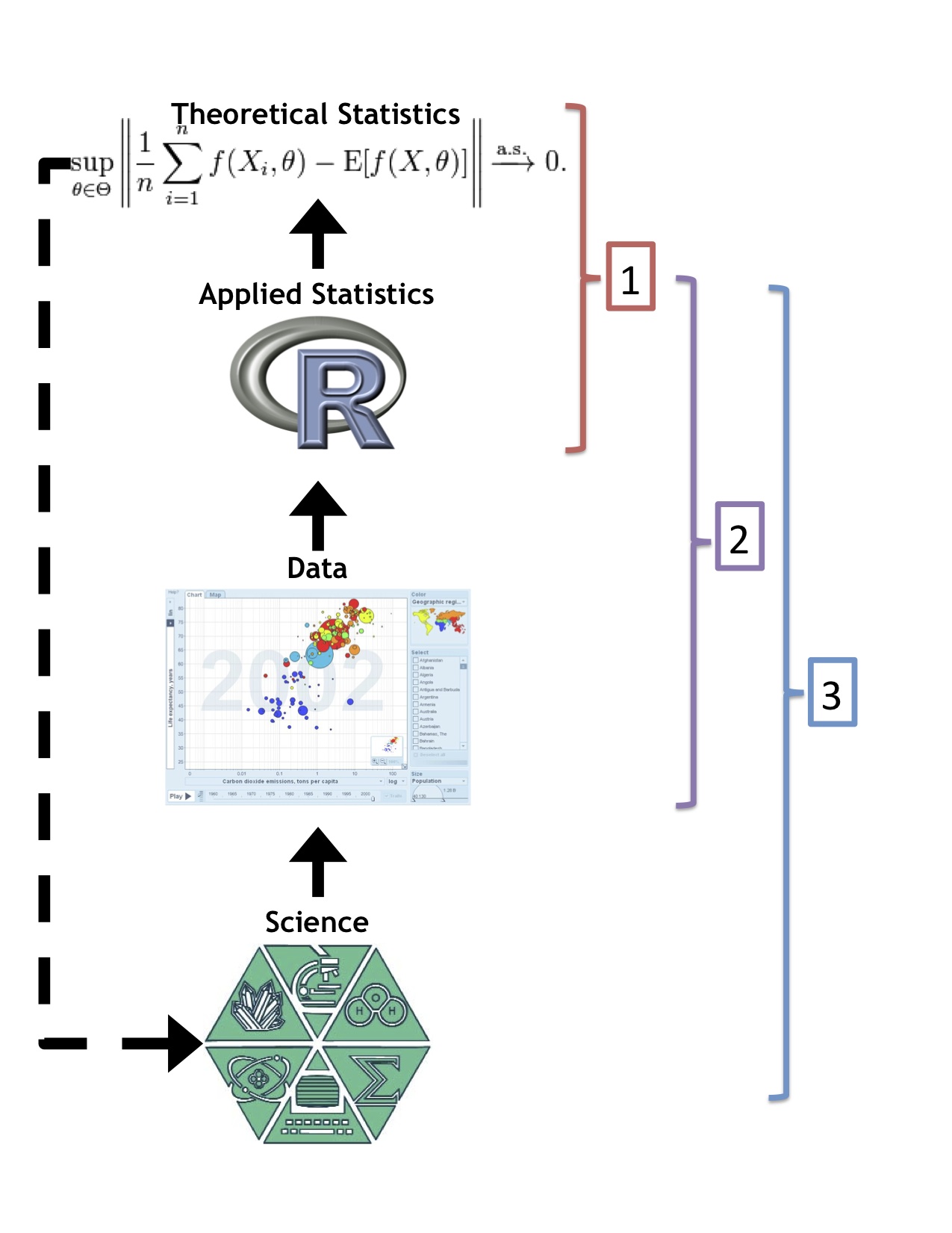

I borrowed a page out of Roger’s book and made a little diagram to illustrate my ideas (actually I can’t even claim credit, it was Roger’s idea to make the diagram). The diagram shows the rough relationship of science, data, applied statistics, and theoretical statistics. Science produces data (although there are other sources), the data are analyzed using applied statistical methods, and theoretical statistics concerns the math behind statistical methods. The dotted line indicates that theoretical statistics ostensibly generalizes applied statistical methods so they can be applied in other disciplines. I do think that this type of generalization is becoming harder and harder as theoretical statistics becomes farther and farther removed from the underlying science.

Based on this diagram I see three major sources for statistical problems:

- Theoretical statistical problems One component of statistics is developing the mathematical and foundational theory that proves we are doing sensible things. This type of problem often seems to be inspired by popular methods that exists/are developed but lack mathematical detail. Not surprisingly, much of the work in this area is motivated by what is mathematically possible or convenient, rather than by concrete questions that are of concern to the scientific community. This work is important, but the current distance between theoretical statistics and science suggests that the impact will be limited primarily to the theoretical statistics community.

- Applied statistics motivated by convenient sources of data. The best example of this type of problem are the analyses in Freakonomics. Since both big data and small big data are now abundant, anyone with a laptop and an internet connection can download the Google n-gram data, a microarray from GEO , data about your city, or really data about anything and perform an applied analysis. These analyses may not be straightforward for computational/statistical reasons and may even require the development of new methods. These problems are often very interesting/clever and so are often the types of analyses you hear about in newspaper articles about “Big Data”. But they may often be misleading or incorrect, since the underlying questions are not necessarily well founded in scientific questions.

- Applied statistics problems motivated by scientific problems. The final category of statistics problems are those that are motivated by concrete scientific questions. The new sources of big data don’t necessarily make these problems any easier. They still start with a specific question for which the data may not be convenient and the math is often intractable. But the potential impact of solving a concrete scientific problem is huge, especially if many people who are generating data have a similar problem. Some examples of problems like this are: can we tell if one batch of beer is better than another, how are quantitative characteristics inherited from parent to child, which treatment is better when some people are censored, how do we estimate variance when we don’t know the distribution of the data, or how do we know which variable is important when we have millions?

So this leads back to the question, what are the biggest open problems in statistics? I would define these problems as the “high potential impact” problems from category 3. To answer this question, I think we need to ask ourselves, what are the most common problems people are trying to solve with data but can’t with what is available right now? Roger nailed this when he talked about the role of statisticians in the science club.

Here are a few ideas that could potentially turn into high-impact statistical problems, maybe our readers can think of better ones?

- How do we credential students taking online courses at a huge scale?

- How do we communicate risk about personalized medicine (or anything else) to a general population without statistical training?

- Can you use social media as a preventative health tool?

- Can we perform randomized trials to improve public policy?

Image Credits: The Science Logo is the old logo for the USU College of Science, the R is the logo for the R statistical programming language, the data image is a screenshot of Gapminder, and the theoretical statistics image comes from the Wikipedia page on the law of large numbers.

Edit: I just noticed this paper, which seems to support some of the discussion above. On the other hand, I think just saying lots of equations = less citations falls into category 2 and doesn’t get at the heart of the problem.