Andrew Gelman’s recent post on what he calls the “scientific mass production of spurious statistical significance” reminded me of a thought I had back when I read John Ioannidis’ paper claiming that most published research finding are false. Many authors, which I will refer to as the pessimists, have joined Ioannidis in making similar claims and repeatedly blaming the current state of affairs on the mindless use of frequentist inference. The gist of my thought is that, for some scientific fields, the pessimist’s criticism is missing a critical point: that in practice, there is an inverse relationship between increasing rates of true discoveries and decreasing rates of false discoveries and that true discoveries from fields such as the biomedical sciences provide an enormous benefit to society. Before I explain this in more detail, I want to be very clear that I do think that reducing false discoveries is an important endeavor and that some of these false discoveries are completely avoidable. But, as I describe below, a general solution that improves the current situation is much more complicated than simply abandoning the frequentist inference that currently dominates.

Few will deny that our current system, with all its flaws, still produces important discoveries. Many of the pessimists’ proposals for reducing false positives seem to be, in one way or another, a call for being more conservative in reporting findings. Example of recommendations include that we require larger effect sizes or smaller p-values, that we correct for the “researcher degrees of freedom”, and that we use Bayesian analyses with pessimistic priors. I tend to agree with many of these recommendations but I have yet to see a specific proposal on exactly how conservative we should be. Note that we could easily bring the false positives all the way down to 0 by simply taking this recommendation to its extreme and stop publishing biomedical research results all together. This absurd proposal brings me to receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

ROC curves plot true positive rates (TPR) versus false positive rates (FPR) for a given classifying procedure. For example, suppose a regulatory agency that runs randomized trials on drugs (e.g. FDA) classifies a drug as effective when a pre-determined statistical test produces a p-value < 0.05 or a posterior probability > 0.95. This procedure will have a historical false positive rate and true positive rate pair: one point in an ROC curve. We can change the 0.05 to, say, 0.2 (or the 0.95 to 0.80) and we would move up the ROC curve: higher FPR and TPR. Not doing research would put us at the useless bottom left corner. It is important to keep in mind that biomedical science is done by imperfect humans on imperfect and stochastic measurements so to make discoveries the field has to tolerate some false discoveries (ROC curves don’t shoot straight up from 0% to 100%). Also note that it can take years to figure out which publications report important true discoveries.

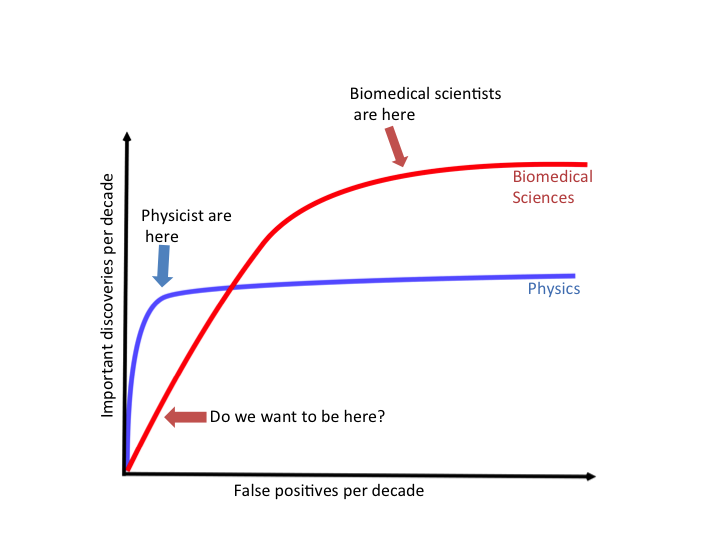

I am going to use the concept of ROC curve to distinguish between reducing FPR by being statistically more conservative and reducing FPR via more general improvements. In my ROC curve the y-axis represents the number of important discoveries per decade and the x-axis the number of false positives per decade (to avoid confusion I will continue to use the acronyms TPR and FPR). The current state of biomedical research is represented by one point on the red curve: one TPR,FPR pair. The pessimist argue that the FPR is close to 100% of all results but they rarely comment on the TPR. Being more conservative lowers our FPR, which saves us time and money, but it also lowers our TPR, which could reduce the number of important discoveries that improve human health. So what is the optimal balance and how far are we from it? I don’t think this is an easy question to answer.

Now, one thing we can all agree on is that moving the ROC curve up is a good thing, since it means that we get a higher TPR for any given FPR. Examples of ways we can achieve this are developing better measurement technologies, statistically improving the quality of these measurements, augmenting the statistical training of researchers, thinking harder about the hypotheses we test, and making less coding or experimental mistakes. However, applying a more conservative procedure does not move the ROC up, it moves our point left on the existing ROC: we reduce our FPR but reduce our TPR as well.

In the plot above I draw two imagined ROC curves: one for physics and one for biomedical research. The physicists’ curve looks great. Note that it shoots up really fast which means they can make most available discoveries with very few false positives. Perhaps due to the maturity of the field, physicists can afford and tend to use very stringent criteria. The biomedical research curve does not look as good. This is mainly due to the fact that biology is way more complex and harder to model mathematically than physics. However, because there is a larger uncharted territory and more research funding, I argue that the rate of discoveries is higher in biomedical research than in physics. But, to achieve this higher TPR, biomedical research has to tolerate a higher FPR. According to my imaginary ROC curves, if we become as stringent as physicists our TPR would be five times smaller. It is not obvious to me that this would result in a better situation than the current one. At the same time, note that the red ROC suggests that increasing the FPR, with the hopes of increasing our TPR, is not a good idea because the curve is quite flat beyond our current location on the curve.

Clearly I am oversimplifying a very complicated issue, but I think it is important to point out that there are two discussions to be had: 1) where should we be on the ROC curve (keeping in mind the relationship between FPR and TPR)? and 2) what can we do to improve the ROC curve? My own view is that we can probably move down the ROC curve some and reduce the FPR without much loss in TPR (for example, by raising awareness of the researcher degrees of freedom). But I also think that most our efforts should go to reducing the FPR by improving the ROC. In general, I think statisticians can add to the conversation about 1) while at the same time continue collaborating to move the red ROC curve up.