Editor’s note: This is a previously published post of mine from a couple of years ago (!). I always thought about turning it into a paper. The interesting idea (I think) is how the causal model matters for whether the lasso or the marginal regression approach works better. Also check it out, the Leekasso is part of the SuperLearner package.

One incredibly popular tool for the analysis of high-dimensional data is the lasso. The lasso is commonly used in cases when you have many more predictors than independent samples (the n « p) problem. It is also often used in the context of prediction.

Suppose you have an outcome Y and several predictors X1,…,XM, the lasso fits a model:

Y = B0 + B1 X1 + B2 X2 + … + BM XM + E

subject to a constraint on the sum of the absolute value of the B coefficients. The result is that: (1) some of the coefficients get set to zero, and those variables drop out of the model, (2) other coefficients are “shrunk” toward zero. Dropping some variables is good because there are a lot of potentially unimportant variables. Shrinking coefficients may be good, since the big coefficients might be just the ones that were really big by random chance (this is related to Andrew Gelman’s type M errors).

I work in genomics, where n«p problems come up all the time. Whenever I use the lasso or when I read papers where the lasso is used for prediction, I always think: “How does this compare to just using the top 10 most significant predictors?” I have asked this out loud enough that some people around here started calling it the “Leekasso” to poke fun at me. So I’m going to call it that in a thinly veiled attempt to avoid Stigler’s law of eponymy (actually Rafa points out that using this name is a perfect example of this law, since this feature selection approach has been proposed before at least once).

Here is how the Leekasso works. You fit each of the models:

Y = B0 + BkXk + E

take the 10 variables with the smallest p-values from testing the Bk coefficients, then fit a linear model with just those 10 coefficients. You never use 9 or 11, the Leekasso is always 10.

For fun I did an experiment to compare the accuracy of the Leekasso and the Lasso.

Here is the setup:

- I simulated 500 variables and 100 samples for each study, each N(0,1)

- I created an outcome that was 0 for the first 50 samples, 1 for the last 50

- I set a certain number of variables (between 5 and 50) to be associated with the outcome using the model Xi = b0i + b1iY + e (this is an important choice, more later in the post)

- I tried different levels of signal to the truly predictive features

- I generated two data sets (training and test) from the exact same model for each scenario

- I fit the Lasso using the lars package, choosing the shrinkage parameter as the value that minimized the cross-validation MSE in the training set

- I fit the Leekasso and the Lasso on the training sets and evaluated accuracy on the test sets.

The R code for this analysis is available here and the resulting data is here.

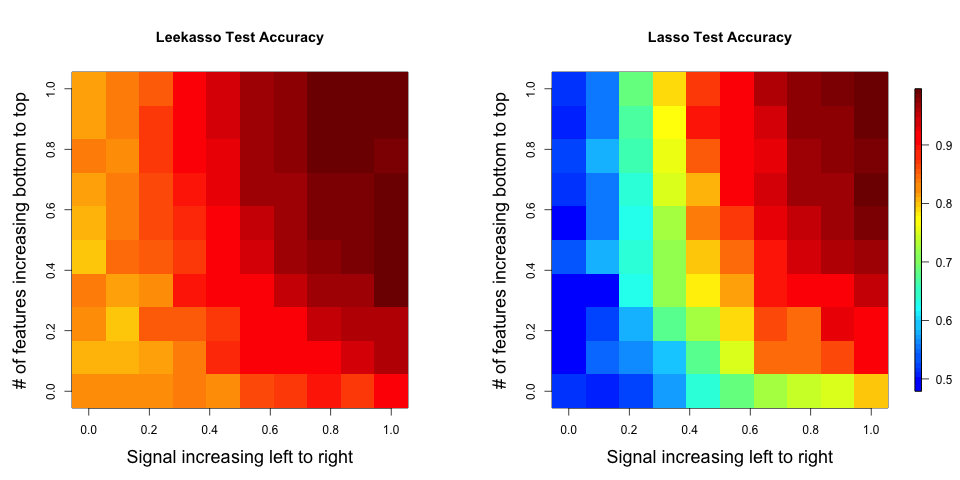

The results show that for all configurations, using the top 10 has a higher out of sample prediction accuracy than the lasso. A larger version of the plot is here.

Interestingly, this is true even when there are fewer than 10 real features in the data or when there are many more than 10 real features ((remember the Leekasso always picks 10).

Some thoughts on this analysis:

- This is only test-set prediction accuracy, it says nothing about selecting the “right” features for prediction.

- The Leekasso took about 0.03 seconds to fit and test per data set compared to about 5.61 seconds for the Lasso.

- The data generating model is the model underlying the top 10, so it isn’t surprising it has higher performance. Note that I simulated from the model: Xi = b0i + b1iY + e, this is the model commonly assumed in differential expression analysis (genomics) or voxel-wise analysis (fMRI). Alternatively I could have simulated from the model: Y = B0 + B1 X1 + B2 X2 + … + BM XM + E, where most of the coefficients are zero. In this case, the Lasso would outperform the top 10 (data not shown). This is a key, and possibly obvious, issue raised by this simulation. When doing prediction differences in the true “causal” model matter a lot. So if we believe the “top 10 model” holds in many high-dimensional settings, then it may be the case that regularization approaches don’t work well for prediction and vice versa.

- I think what may be happening is that the Lasso is overshrinking the parameter estimates, in other words, you give up too much bias for a gain in variance. Alan Dabney and John Storey have a really nice paper discussing shrinkage in the context of genomic prediction that I think is related.