Editor’s note - This is a chapter from my book How to be a modern scientist where I talk about some of the tools and techniques that scientists have available to them now that they didn’t before.

Writing - what should I do and why?

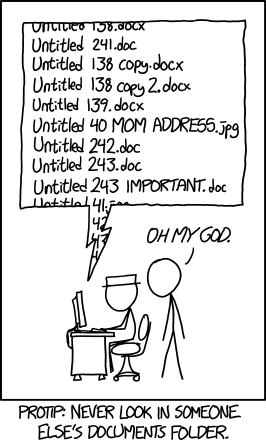

Write using collaborative software to avoid version control issues.

On almost all modern scientific papers you will have co-authors. The traditional way of handling this was to create a single working document and pass it around. Unfortunately this system always results in a long collection of versions of a manuscript, which are often hard to distinguish and definitely hard to synthesize.

An alternative approach is to use formal version control systems like Git and Github. However, the overhead for using these systems can be pretty heavy for paper authoring. They also require all parties participating in the writing of the paper to be familiar with version control and the command line. Alternative paper authoring tools are now available that provide some of the advantages of version control without the major overhead involved in using base version control systems.

Make figures the focus of your writing

Once you have a set of results and are ready to start writing up the paper the first thing is not to write. The first thing you should do is create a set of 1-10 publication-quality plots with 3-4 as the central focus (see Chapter 10 here for more information on how to make plots). Show these to someone you trust to make sure they “get” your story before proceeding. Your writing should then be focused around explaining the story of those plots to your audience. Many people, when reading papers, read the title, the abstract, and then usually jump to the figures. If your figures tell the whole story you will dramatically increase your audience. It also helps you to clarify what you are writing about.

Write clearly and simply even though it may make your papers harder to publish.

Learn how to write papers in a very clear and simple style. Whenever you can write in plain English and make the approach you are using understandable and clear. This can (sometimes) make it harder to get your papers into journals. Referees are trained to find things to criticize and by simplifying your argument they will assume that what you have done is easy or just like what has been done before. This can be extremely frustrating during the peer review process. But the peer review process isn’t the end goal of publishing! The point of publishing is to communicate your results to your community and beyond so they can use them. Simple, clear language leads to much higher use/reading/citation/impact of your work.

Include links to code, data, and software in your writing

Not everyone recognizes the value of re-analysis, scientific software, or data and code sharing. But it is the fundamental cornerstone of the modern scientific process to make all of your materials easily accessible, re-usable and checkable. Include links to data, code, and software prominently in your abstract, introduction and methods and you will dramatically increase the use and impact of your work.

Give credit to others

In academics the main currency we use is credit for publication. In general assigning authorship and getting credit can be a very tricky component of the publication process. It is almost always better to err on the side of offering credit. A very useful test that my advisor John Storey taught me is if you are embarrassed to explain the authorship credit to anyone who was on the paper or not on the paper, then you probably haven’t shared enough credit.

Writing - what tools should I use?

WYSIWYG software: Google Docs and Paperpile.

This system uses Google Docs for writing and Paperpile for reference management. If you have a Google account you can easily create documents and share them with your collaborators either privately or publicly. Paperpile allows you to search for academic articles and insert references into the text using a system that will be familiar if you have previously used Endnote and Microsoft Word.

This system has the advantage of being a what you see is what you get system - anyone with basic text processing skills should be immediately able to contribute. Google Docs also automatically saves versions of your work so that you can flip back to older versions if someone makes a mistake. You can also easily see which part of the document was written by which person and add comments.

Getting started

- Set up accounts with Google and with Paperpile. If you are an academic the Paperpile account will cost $2.99 a month, but there is a 30 day free trial.

- Go to Google Docs and create a new document.

- Set up the Paperpile add-on for Google Docs

- In the upper right hand corner of the document, click on the Share link and share the document with your collaborators

- Start editing

- When you want to include a reference, place the cursor where you want the reference to go, then using the Paperpile menu, choose insert citation. This should give you a search box where you can search by Pubmed ID or on the web for the reference you want.

- Once you have added some references use the Citation style option under Paperpile to pick the citation style for the journal you care about.

- Then use the Format citations option under Paperpile to create the bibliography at the end of the document

The nice thing about using this system is that everyone can easily directly edit the document simultaneously - which reduces conflict and difficulty of use. A disadvantage is getting the formatting just right for most journals is nearly impossible, so you will be sending in a version of your paper that is somewhat generic. For most journals this isn’t a problem, but a few journals are sticklers about this.

Typesetting software: Overleaf or ShareLatex

An alternative approach is to use typesetting software like Latex. This requires a little bit more technical expertise since you need to understand the Latex typesetting language. But it allows for more precise control over what the document will look like. Using Latex on its own you will have many of the same issues with version control that you would have for a word document. Fortunately there are now “Google Docs like” solutions for editing latex code that are readily available. Two of the most popular are Overleaf and ShareLatex.

In either system you can create a document, share it with collaborators, and edit it in a similar manner to a Google Doc, with simultaneous editing. Under both systems you can save versions of your document easily as you move along so you can quickly return to older versions if mistakes are made.

I have used both kinds of software, but now primarily use Overleaf because they have a killer feature. Once you have finished writing your paper you can directly submit it to some preprint servers like arXiv or biorXiv and even some journals like Peerj or f1000research.

Getting started

- Create an Overleaf account. There is a free version of the software. Paying $8/month will give you easy saving to Dropbox.

- Click on New Project to create a new document and select from the available templates

- Open your document and start editing

- Share with colleagues by clicking on the Share button within the project. You can share either a read only version or a read and edit version.

Once you have finished writing your document you can click on the Publish button to automatically submit your paper to the available preprint servers and journals. Or you can download a pdf version of your document and submit it to any other journal.

Writing - further tips and issues

When to write your first paper

As soon as possible! The purpose of graduate school is (in some order):

- Freedom

- Time to discover new knowledge

- Time to dive deep

- Opportunity for leadership

- Opportunity to make a name for yourself

- R packages

- Papers

- Blogs

- Get a job

The first couple of years of graduate school are typically focused on (1) teaching you all the technical skills you need and (2) data dumping as much hard-won practical experience from more experienced people into your head as fast as possible.

After that one of your main focuses should be on establishing your own program of research and reputation. Especially for Ph.D. students it can not be emphasized enough no one will care about your grades in graduate school but everyone will care what you produced. See for example, Sherri’s excellent guide on CV’s for academic positions.

I firmly believe that R packages and blog posts can be just as important as papers, but the primary signal to most traditional academic communities still remains published peer-reviewed papers. So you should get started on writing them as soon as you can (definitely before you feel comfortable enough to try to write one).

Even if you aren’t going to be in academics, papers are a great way to show off that you can (a) identify a useful project, (b) finish a project, and (c) write well. So the first thing you should be asking when you start a project is “what paper are we working on?”

What is an academic paper?

A scientific paper can be distilled into four parts:

- A set of methodologies

- A description of data

- A set of results

- A set of claims

When you (or anyone else) writes a paper the goal is to communicate clearly items 1-3 so that they can justify the set of claims you are making. Before you can even write down 4 you have to do 1-3. So that is where you start when writing a paper.

How do you start a paper?

The first thing you do is you decide on a problem to work on. This can be a problem that your advisor thought of or it can be a problem you are interested in, or a combination of both. Ideally your first project will have the following characteristics:

- Concrete

- Solves a scientific problem

- Gives you an opportunity to learn something new

- Something you feel ownership of

- Something you want to work on

Points 4 and 5 can’t be emphasized enough. Others can try to help you come up with a problem, but if you don’t feel like it is your problem it will make writing the first paper a total slog. You want to find an option where you are just insanely curious to know the answer at the end, to the point where you just have to figure it out and kind of don’t care what the answer is. That doesn’t always happen, but that makes the grind of writing papers go down a lot easier.

Once you have a problem the next step is to actually do the research. I’ll leave this for another guide, but the basic idea is that you want to follow the usual data analytic process:

- Define the question

- Get/tidy the data

- Explore the data

- Build/borrow a model

- Perform the analysis

- Check/critique results

- Write things up

The hardest part for the first paper is often knowing where to stop and start writing.

How do you know when to start writing?

Sometimes this is an easy question to answer. If you started with a very concrete question at the beginning then once you have done enough analysis to convince yourself that you have the answer to the question. If the answer to the question is interesting/surprising then it is time to stop and write.

If you started with a question that wasn’t so concrete then it gets a little trickier. The basic idea here is that you have convinced yourself you have a result that is worth reporting. Usually this takes the form of between 1 and 5 figures that show a coherent story that you could explain to someone in your field.

In general one thing you should be working on in graduate school is your own internal timer that tells you, “ok we have done enough, time to write this up”. I found this one of the hardest things to learn, but if you are going to stay in academics it is a critical skill. There are rarely deadlines for paper writing (unless you are submitting to CS conferences) so it will eventually be up to you when to start writing. If you don’t have a good clock, this can really slow down your ability to get things published and promoted in academics.

One good principle to keep in mind is “the perfect is the enemy of the very good” Another one is that a published paper in a respectable journal beats a paper you just never submit because you want to get it into the “best” journal.

A note on “negative results”

If the answer to your research problem isn’t interesting/surprising but you started with a concrete question it is also time to stop and write. But things often get more tricky with this type of paper as most journals when reviewing papers filter for “interest” so sometimes a paper without a really “big” result will be harder to publish. This is ok!! Even though it may take longer to publish the paper, it is important to publish even results that aren’t surprising/novel. I would much rather that you come to an answer you are comfortable with and we go through a little pain trying to get it published than you keep pushing until you get an “interesting” result, which may or may not be justifiable.

How do you start writing?

- Once you have a set of results and are ready to start writing up the paper the first thing is not to write. The first thing you should do is create a set of 1-4 publication-quality plots (see Chapter 10 here). Show these to someone you trust to make sure they “get” your story before proceeding.

- Start a project on Overleaf or Google Docs.

- Write up a story around the four plots in the simplest language you feel you can get away with, while still reporting all of the technical details that you can.

- Go back and add references in only after you have finished the whole first draft.

- Add in additional technical detail in the supplementary material if you need it.

- Write up a reproducible version of your code that returns exactly the same numbers/figures in your paper with no input parameters needed.

What are the sections in a paper?

Keep in mind that most people will read the title of your paper only, a small fraction of those people will read the abstract, a small fraction of those people will read the introduction, and a small fraction of those people will read your whole paper. So make sure you get to the point quickly!

The sections of a paper are always some variation on the following:

- Title: Should be very short, no colons if possible, and state the main result. Example, “A new method for sequencing data that shows how to cure cancer”. Here you want to make sure people will read the paper without overselling your results - this is a delicate balance.

- Abstract: In (ideally) 4-5 sentences explain (a) what problem you are solving, (b) why people should care, (c) how you solved the problem, (d) what are the results and (e) a link to any data/resources/software you generated.

- Introduction: A more lengthy (1-3 pages) explanation of the problem you are solving, why people should care, and how you are solving it. Here you also review what other people have done in the area. The most critical thing is never underestimate how little people know or care about what you are working on. It is your job to explain to them why they should.

- Methods: You should state and explain your experimental procedures, how you collected results, your statistical model, and any strengths or weaknesses of your proposed approach.

- Comparisons (for methods papers): Compare your proposed approach to the state of the art methods. Do this with simulations (where you know the right answer) and data you haven’t simulated (where you don’t know the right answer). If you can base your simulation on data, even better. Make sure you are simulating both the easy case (where your method should be great) and harder cases where your method might be terrible.

- Your analysis: Explain what you did, what data you collected, how you processed it and how you analysed it.

- Conclusions: Summarize what you did and explain why what you did is important one more time.

- Supplementary Information: If there are a lot of technical computational, experimental or statistical details, you can include a supplement that has all of the details so folks can follow along. As far as possible, try to include the detail in the main text but explained clearly.

The length of the paper will depend a lot on which journal you are targeting. In general the shorter/more concise the better. But unless you are shooting for a really glossy journal you should try to include the details in the paper itself. This means most papers will be in the 4-15 page range, but with a huge variance.

Note: Part of this chapter appeared in the Leek group guide to writing your first paper