Buzzfeed recently published a long article on the struggles of the secretive data science company, Palantir.

Over the last 13 months, at least three top-tier corporate clients have walked away, including Coca-Cola, American Express, and Nasdaq, according to internal documents. Palantir mines data to help companies make more money, but clients have balked at its high prices that can exceed $1 million per month, expressed doubts that its software can produce valuable insights over time, and even experienced difficult working relationships with Palantir’s young engineers. Palantir insiders have bemoaned the “low-vision” clients who decide to take their business elsewhere.

Palantir’s origins are with PayPal, and its founders are part of the PayPal Mafia. As Peter Thiel describes it in his book Zero to One, PayPal was having a lot of trouble with fraud and the FBI was getting on its case. So PayPal developed some software to monitor the millions of transacations going through its systems and to flag transactions that were suspicious. Eventually, they realized that this kind of software might be useful to government agencies in a variety of contexts and the idea for Palantir was born.

Much of the press reaction to Buzzfeed’s article amounts to schadenfreude over the potential fall of another so-called Silicon Valley unicorn. Indeed, Palentir is valued at $20 billion, a valuation only exceeded in the private markets by Airbnb and Uber. But to me, nothing in the article indicates that Palantir is necessarily more poorly run than your average startup. It looks like they are going through pretty standard growing pains, trying to scale the business and diversify the customer base. It’s not surprising to me that employees would leave at this point—going from startup to “real company” is often not that fun and just a lot of work.

However, a key question that arises is that if Palantir is having trouble trying to scale the business, why might that be? The Buzzfeed article doesn’t contain any answers but in this post I will attempt to speculate.

The real message from the Buzzfeed article goes beyond just Palantir and is highly relevant to the data science world. It ultimately comes down to the question of what is the value of data analysis?, and secondarily, how do you communicate that value?

The Data Science Spectrum

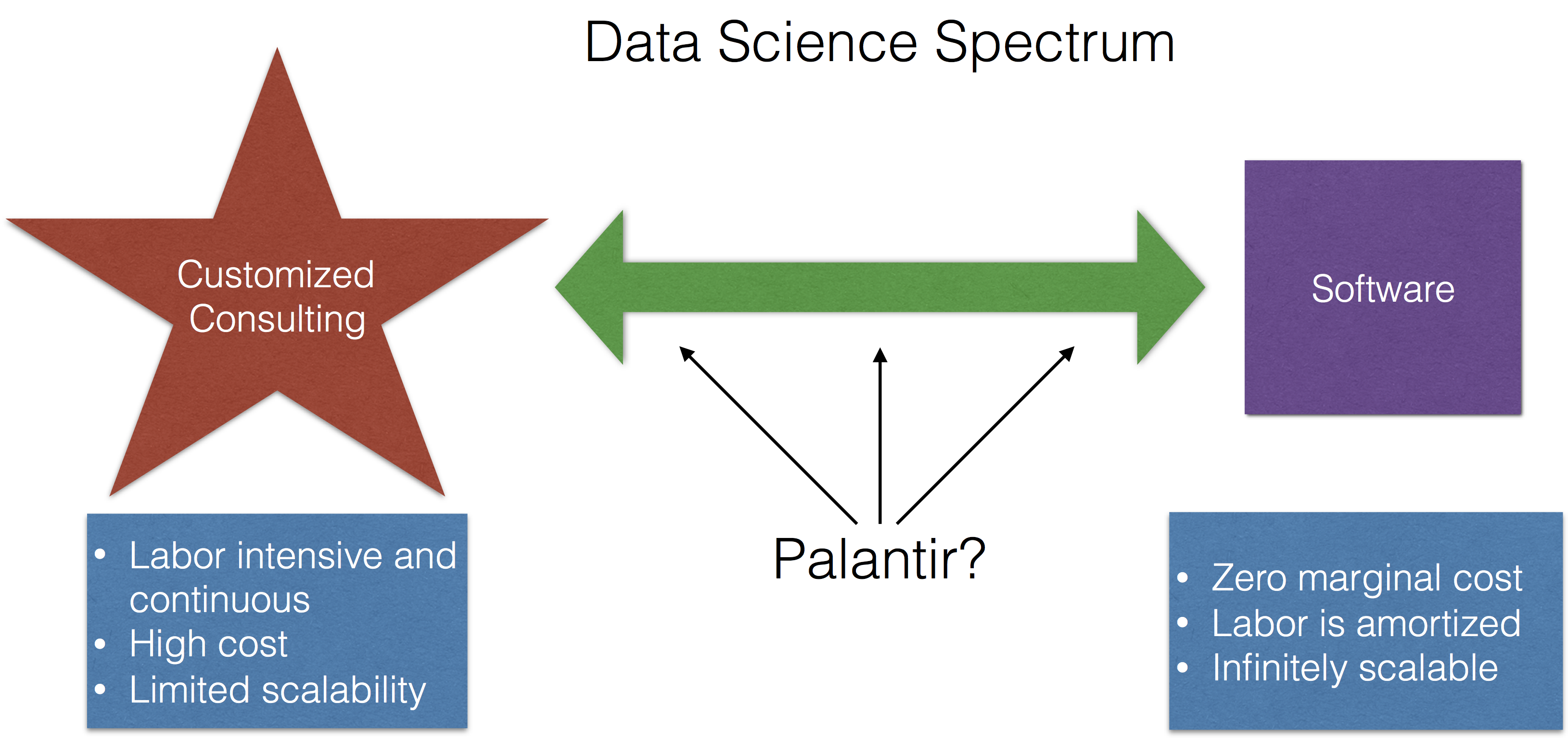

Data science activities live on a spectrum with software on one end and highly customized consulting on another end (I lump a lot of things into consulting, including methods development, modeling, etc.).

The idea being that if someone comes to you with a data problem, there are two extremes that you might offer to them:

- Give them some software, some documentation, and maybe a brief tutorial on how to use the software, and then send them on their way. For example, if someone wants to see if two groups are different from each other, you could send them the

t.test()function in R and explain how to use it. This could be done over email; you wouldn’t even have to talk to the person. - Meet with the person, talk about their problem and the question they’re trying to answer, develop an analysis plan, and build a custom software solution that produces the exact output that they’re looking for.

The first option is cheap, simple, and if you had a good enough web site, the person probably wouldn’t even have to talk with you at all! For example, I use this web site for sample size calculations and I’ve never spoken with the author of the web site. Much of the labor is up front, for the development of the software, and then is amortized over the life of the product. Ultimately, a software product has zero marginal cost and so it can be easily replicated and is infinitely scalable.

The second option is labor intensive, time-consuming, ongoing in nature, and is only scalable to the extent that you are willing to forgo sleep and maybe bend the space-time continuum. By definition, a custom solution is unique and is difficult to replicate.

Selling Data Science

An important question for Palantir and data scientists in general is “How do you communicate the value of data analysis?” Many people expect the result of a good data analysis to be something “surprising”, i.e. something that they didn’t already know. Because if they knew it already why bother looking at the data? Think Moneyball—if you can find that “diamond in the rough” it make spending the time to analyze the data worthwhile. But the success of a data analysis can’t depend on the results. What if you go through the data and find nothing? Is the data analysis a failure? We as data scientists can only show what the data show. Otherwise, it just becomes a recipe for telling people what they want to hear.

It’s tempting for a client to say “well, the data didn’t show anything surprising so there’s no value there.” Also, a data analysis may reveal something that is perhaps interesting but doesn’t necessarily lead to any sort of decision. For example, there may be an aspect of a business process that is inefficient but is nevertheless unmodifiable. There may be little perceived value in discovering this with data.

What is Useful?

Palantir apparently tried to develop a relationship with American Express, but ultimately failed.

But some major firms have not found Palantir’s products and services that useful. In April 2015, employees were informed that American Express (codename: Charlie’s Angels) had dumped Palantir after 18 months of cybersecurity work, including a six-month pilot, an email shows. “We struggled from day 1 to make Palantir a sticky product for users and generate wins,” Sid Rajgarhia, a Palantir business development employee, said in the email.

What does it mean for a data analysis product to be useful? It’s not necessarily clear to me in this case. Did Palantir not reveal new information? Did they not highlight something that could be modified?

Lack of Deep Expertise

A failed attempt attempt at working with Coke reveals some other challenges of the data science business model.

The beverage giant also had other concerns [in addition to the price]. Coke “wanted deeper industry expertise in a partner,” Jonty Kelt, a Palantir executive, told colleagues in the email. He added that Coca-Cola’s “working relationship” with the youthful Palantir employees was “difficult.” The Coke executive acknowledged that the beverage giant “needs to get better at working with millennials,” according to Kelt. Coke spokesperson Scott Williamson declined to comment.

Annoying millenials notwithstanding, it’s clear that Coke didn’t feel comfortable collaborating with Palantir’s personnel. Like any data science collaboration, it’s key that the data scientist have some familiarity with the domain. In many cases, having “deep expertise” in an area can give a collaborator confidence that you will focus on the things that matter to them. But developing that expertise costs money and time and it may prevent you from working with other types of clients where you will necessarily have less expertise. For example, Palantir’s long experience working with the US military and intelligence agencies gave them deep expertise in those areas, but how does that help them with a consumer products company?

Harder Than It Looks

The final example of a client that backed out is Kimberly-Clark:

But Kimberly-Clark was getting cold feet by early 2016. In January, a year after the initial pilot, Kimberly-Clark executive Anthony J. Palmer said he still wasn’t ready to sign a binding contract, meeting notes show. Palmer also “confirmed our suspicion” that a primary reason Kimberly-Clark had not moved forward was that “they wanted to see if they could do it cheaper themselves,” Kelt told colleagues in January. [emphasis added]

This is a common problem confronted by anyone in the data science business. A good analysis often looks easy in retrospect—all you did was run some functions and put the data through some models! In fact, running the models probably is the easy part, but getting to the point where you can actually fit models can be incredibly hard. Many clients, not seeing the long and winding process leading to a model, will be tempted think they can do it themselves.

Palantir’s Valuation

Ultimately, what makes Palantir interesting is its astounding valuation. But what is the driver of this valuation? I think the key to answering this question lies in the description of the company itself:

The company, based in Palo Alto, California, is essentially a hybrid software and consulting firm, placing what it calls “forward deployed engineers” on-site at client offices.

What does it mean to be a “hybrid software and consulting firm”? And which one is the company more like? Consulting or software? Because ultimately, revealing which side of the spectrum Palantir is really on could have huge implications for its valuation and future prospects.

Consulting companies can surely make a lot of money, but none to my knowledge have the kind of valuation that Palantir currently commands. If it turns out that every customer of Palantir’s requires a custom solution, then I think they’re likely overvalued, because that model scales poorly. On the other hand, if Palantir has genuinely figured out a way to “software-ize” data analysis and to turn it into a commodity, then they are very likely undervalued.

Given the tremendous difficulty of turning data analysis into a software problem, my guess is that they are more akin to a consulting company and are overvalued. This is not to say that they won’t make money—they will likely make plenty—but that they won’t be the Silicon Valley darling that everyone wants them to be.