Over the past year, there have been a number of recurring topics in my global news feed that have a shared theme to them. Some examples of these topics are:

- Fake news: Before and after the election in 2016, Facebook (or Facebook’s Trending News algorithm) was accused of promoting news stories that turned out to be completely false, promoted by dubious news sources in FYROM and elsewhere.

- Theranos: This diagnostic testing company promised to revolutionize the blood testing business and prevent disease for all by making blood testing simple and painless. This way people would not be afraid to get blood tests and would do them more often, presumably catching diseases while they were in the very early stages. Theranos lobbied to allow patients order their own blood tests so that they wouldn’t need a doctor’s order.

- Homeopathy: This a so-called alternative medical system developed in the late 18th century based on notions such as “like cures like” and “law of minimum dose.

- Online education: New companies like Coursera and Udacity promised to revolutionize education by making it accessible to a broader audience than conventional universities were able.

What exactly do these things have in common?

First, consumers love them. Fake news played to people’s biases by confirming to them, from a seemingly trustworthy source, what they always “knew to be true”. The fact that the stories weren’t actually true was irrelevant given that users enjoyed the experience of seeing what they agreed with. Perhaps the best explanation of the entire Facebook fake news issue was from Kim-Mai Cutler:

The best way to have the stickiest and most lucrative product? Be a systematic tool for confirmation bias. https://t.co/8uOHZLomhX

— Kim-Mai Cutler (@kimmaicutler) November 10, 2016

Theranos promised to revolutionize blood testing and change the user experience behind the whole industry. Indeed the company had some fans (particularly amongst its investor base). However, after investigations by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the FDA, and an independent laboratory, it was found that Theranos’s blood testing machine was wildly inconsistent and variable, leading to Theranos ultimately retracting all of its blood test results and cutting half its workforce.

Homeopathy is not company specific, but is touted by many as an “alternative” treatment for many diseases, with many claiming that it “works for them”. However, the NIH states quite clearly on its web site that “There is little evidence to support homeopathy as an effective treatment for any specific condition.”

Finally, companies like Coursera and Udacity in the education space have indeed produced products that people like, but in some instances have hit bumps in the road. Udacity conducted a brief experiment/program with San Jose State University that failed due to the large differences between the population that took online courses and the one that took them in person. Coursera has massive offerings from major universities (including my own) but has run into continuing challenges with drop out and questions over whether the courses offered are suitable for job placement.

User Experience and Value

In each of these four examples there is a consumer product that people love, often because they provide a great user experience. Take the fake news example–people love to read headlines from “trusted” news sources that agree with what they believe. With Theranos, people love to take a blood test that is not painful (maybe “love” is the wrong word here). With many consumer products companies, it is the user experience that defines the value of a product. Often when describing the user experience, you are simultaneously describing the value of the product.

Take for example Uber. With Uber, you open an app on your phone, click a button to order a car, watch the car approach you on your phone with an estimate of how long you will be waiting, get in the car and go to your destination, and get out without having to deal with paying. If someone were to ask me “What’s the value of Uber?” I would probably just repeat the description in the previous sentence. Isn’t it obvious that it’s better than the usual taxi experience? The same could be said for many companies that have recently come up: Airbnb, Amazon, Apple, Google. With many of the products from these companies, the description of the user experience is a description of its value.

Disruption Through User Experience

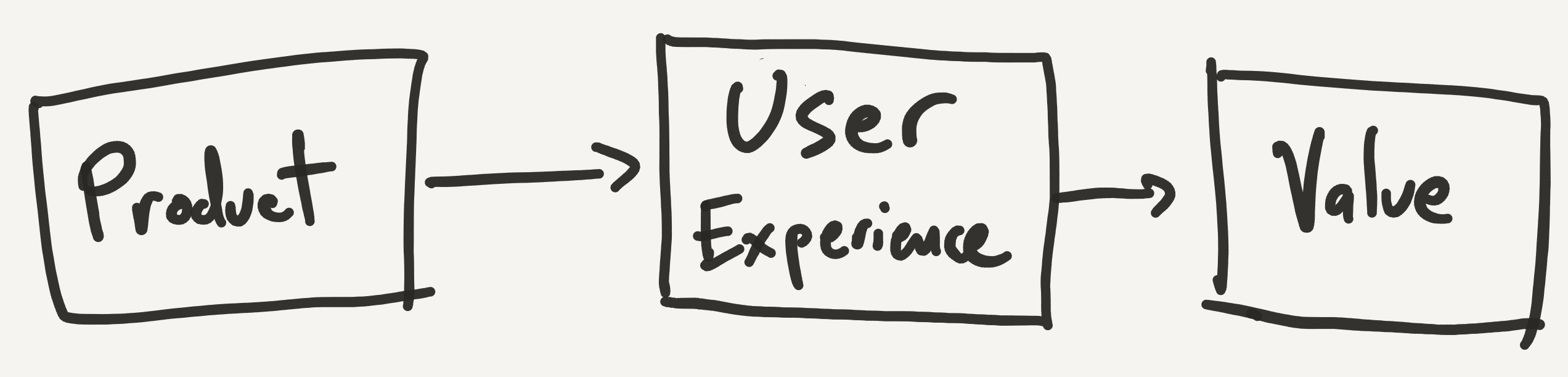

In the example of Uber (and Airbnb, and Amazon, etc.) you could depict the relationship between the product, the user experience, and the value as such:

Any changes that you can make to the product to improve the user experience will then improve the value that the product offers. Another way to say it is that the user experience serves as a surrogate outcome for the value. We can influence the UX and know that we are improving value. Furthermore, any measurements that we take on the UX (surveys, focus groups, app data) will serve as direct observations on the value provided to customers.

New companies in these kinds of consumer product spaces can disrupt the incumbents by providing a much better user experience. When incumbents have gotten fat and lazy, there is often a sizable segment of the customer base that feels underserved. That’s when new companies can swoop in to specifically serve that segment, often with a “worse” product overall (as in fewer features) and usually much cheaper. The Internet has made the “swooping in” much easier by dramatically reducing transaction and distribution costs. Once the new company has a foothold, they can gradually work their way up the ladder of customer segments to take over the market. It’s classic disruption theory a la Clayton Christensen.

When Value Defines the User Experience and Product

There has been much talk of applying the classic disruption model to every space imaginable, but I contend that not all product spaces are the same. In particular, the four examples I described in the beginning of this post cover some of those different areas:

- Medicine (Theranos, homeopathy)

- News (Facebook/fake news)

- Education (Coursera/Udacity)

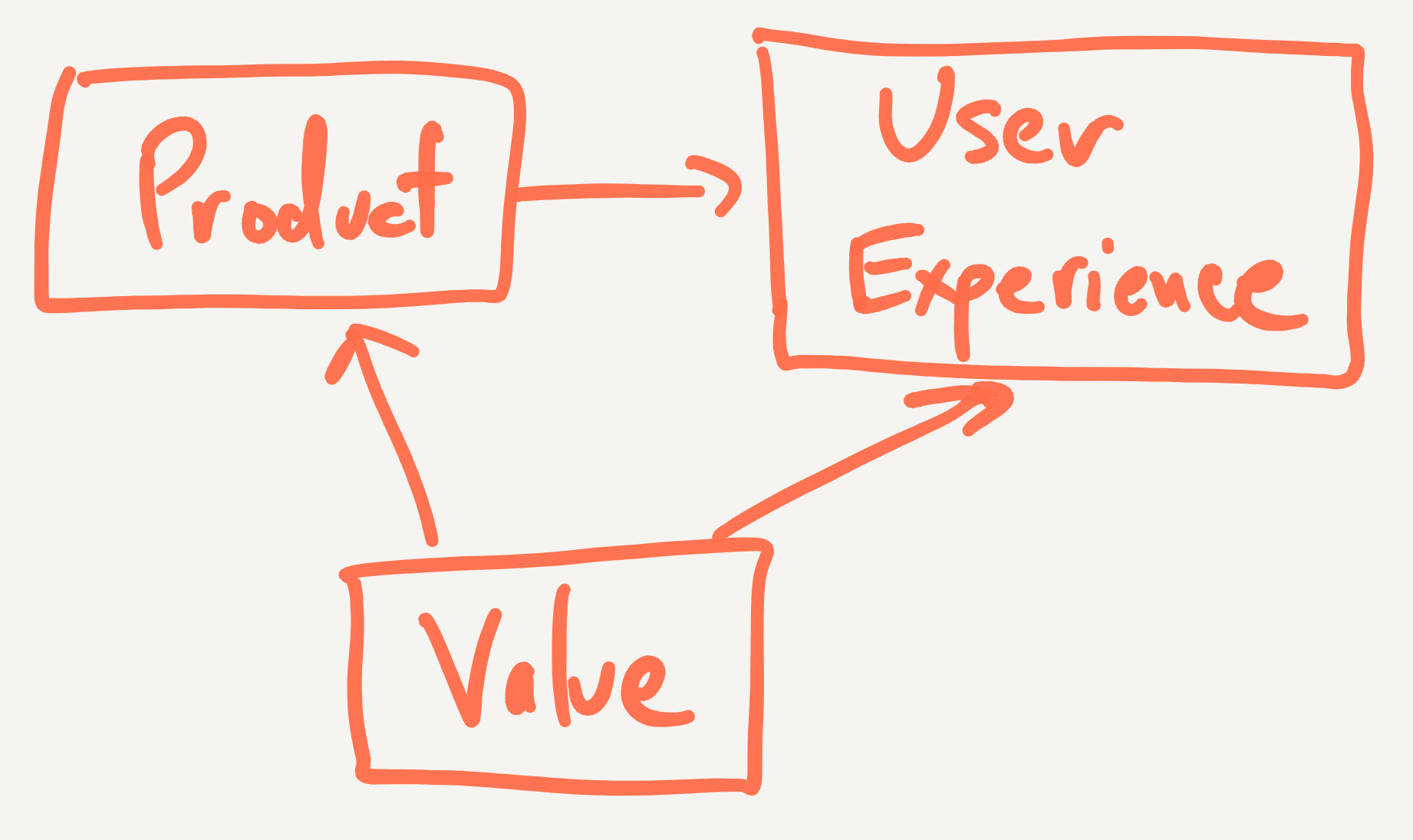

One thing you’ll notice about these areas, particularly with medicine and education, is that they are all heavily regulated. The reason is because we as a community have decided that there is a minimum level of value that is required to be provided by entities in this space. That is, the value that a product offers is defined first, before the product can come to market. Therefore, the value of the product actually constrains the space of products that can be produced. We can depict this relationship as such:

In classic regression modeling language, the value of a product must be “adjusted for” before examining the relationship between the product and the user experience. Naturally, as in any regression problem, when you adjust for a variable that is related to the product and the user experience, you reduce the overall variation in the product.

In situations where the value defines the product and the user experience, there is much less room to maneuver for new entrants in the market. The reason is because they, like everyone else, are constrained by the value that is agreed upon by the community, usually in the form of regulations.

When Theranos comes in and claims that it’s going to dramatically improve the user experience of blood testing, that’s great, but they must be constrained by the value that society demands, which is a certain precision and accuracy in its testing results. Companies in the online education space are welcome to disrupt things by providing a better user experience. Online offerings in fact do this by allowing students to take classes according to their own schedule, wherever they may live in the world. But we still demand that the students learn an agreed-upon set of facts, skills, or lessons.

New companies will often argue that the things that we currently value are outdated or no longer valuable. Their incentive is to change the value required so that there is more room for new companies to enter the space. This is a good thing, but it’s important to realize that this cannot happen solely through changes in the product. Innovative features of a product may help us to understand that we should be valuing different things, but ultimately the change in what we preceive as value occurs independently of any given product.

When I see new companies enter the education, medicine, or news areas, I always hesitate a bit because I want some assurance that they will still provide the value that we have come to expect. In addition, with these particular areas, there is a genuine sense that failing to deliver on what we value could cause serious harm to individuals. However, I think the discussion that is provoked by new companies entering the space is always welcome because we need to constantly re-evaluate what we value and whether it matches the needs of our time.