Rolando Acosta and I recently posted a manuscript on bioRxiv describing the effects of Hurricane María, based on an analysis of mortality data provided by the Demographic Registry. I was also an author on a paper published in May based on a survey of 3,000 households. These are very different datasets. Assuming it is complete, the Demographic Registry dataset provides much more precise quantitative information. However, this dataset was not made publicly available until June 1, 2018, three days after the paper based on the survey data was released. The story of how all this happened is somewhat complex. In this post I describe this process in some detail.

There is also a bit of confusion about why we performed a survey at all, as opposed to using the Demographic Registry as done by other groups. The main reason is that we were not provided the 2017 data and did not know if what was being published was official government data or not. We eventually obtained preliminary 2017 data, after our survey was finished, but, as I show below, these data appeared to be incomplete for November and December. The complete data for 2017 was not released until June 1.

As I was looking through my emails to remind myself of the multiple ways we requested the data, I found that the entire story to be interesting and informative. So I put together an annotated timeline. Note that I might update this list if colleagues or other involved parties send me corrections or more information.

Sep 20 – Hurricane María makes landfall in Puerto Rico.

Sep 20-30 – Reports from friends and family point to a dire situation. None of them have power, few have running water, and some have no way to communicate.

Oct 03 – The president of the USA visits Puerto Rico. In a press conference the governor states that the death count is 16.

“Every death is a horror,” Trump said, “but if you look at a real catastrophe like Katrina and you look at the tremendous – hundreds and hundreds of people that died – and you look at what happened here with, really, a storm that was just totally overpowering … no one has ever seen anything like this.” “What is your death count?” he asked as he turned to Puerto Rico Gov. Ricardo Rosselló. “17?” “16,” Rosselló answered. “16 people certified,” Trump said. “Sixteen people versus in the thousands. You can be very proud of all of your people and all of our people working together.

Oct 3 - 23 - The number 16 did not make sense to me. And if the government is incorrectly assuming things are fine, the response will not be appropriate and people will be at risk. This is when I first decide I should look for daily mortality data as we can probably get a decent estimate from studying the jump right after September 20.

Oct 23 – Dr. Caroline Buckee, the lead author of the survey paper, contacts me for the first time asking if I am interested in helping assess the situation in Puerto Rico. Based on reports from a colleague doing field work in Puerto Rico, she is “concerned that the mortality estimates in Puerto Rico following the hurricane are wildly wrong”. She is already organizing a cluster survey to try to quantify the true mortality caused by the hurricane. I agree to help. We start studying the literature on this topic and thinking about who to collaborate with groups in Puerto Rico.

Oct 31 - Caroline starts contacting people in Puerto Rico asking for help with the survey.

Nov 01 - We start designing the study. For the power calculation it would be convenient to get an idea of a possible range of death rates. We start trying to find public mortality data that can help us do this.

Nov 08 - The New York times publishes an article based on funeral home data confirming our suspicion that the situation in Puerto Rico is much worse than was reported on October 3.

Nov 14 – Not having any luck finding official government data online I email the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics (PRIS) asking for help.

Nov 16 – PRIS replies that the Demographic Registry has these data. They email the directory of the Demographic Registry on our behalf.

Nov 20 – CNN publishes an article describing a funeral home survey estimates. They estimate about 499 excess deaths.

Nov 21 – The Penn State University (PSU) study with the first estimate of excess deaths based on mortality data is posted on SocArXiv They estimate about 1,000 excess deaths. This estimate is based on historical data from 2010-2016 and a count for September 2017 that the authors obtained from a public statement made by Puerto Rico’s Public Security Secretary.

Nov 27 - I email the corresponding author of the PSU study asking if they have the data.

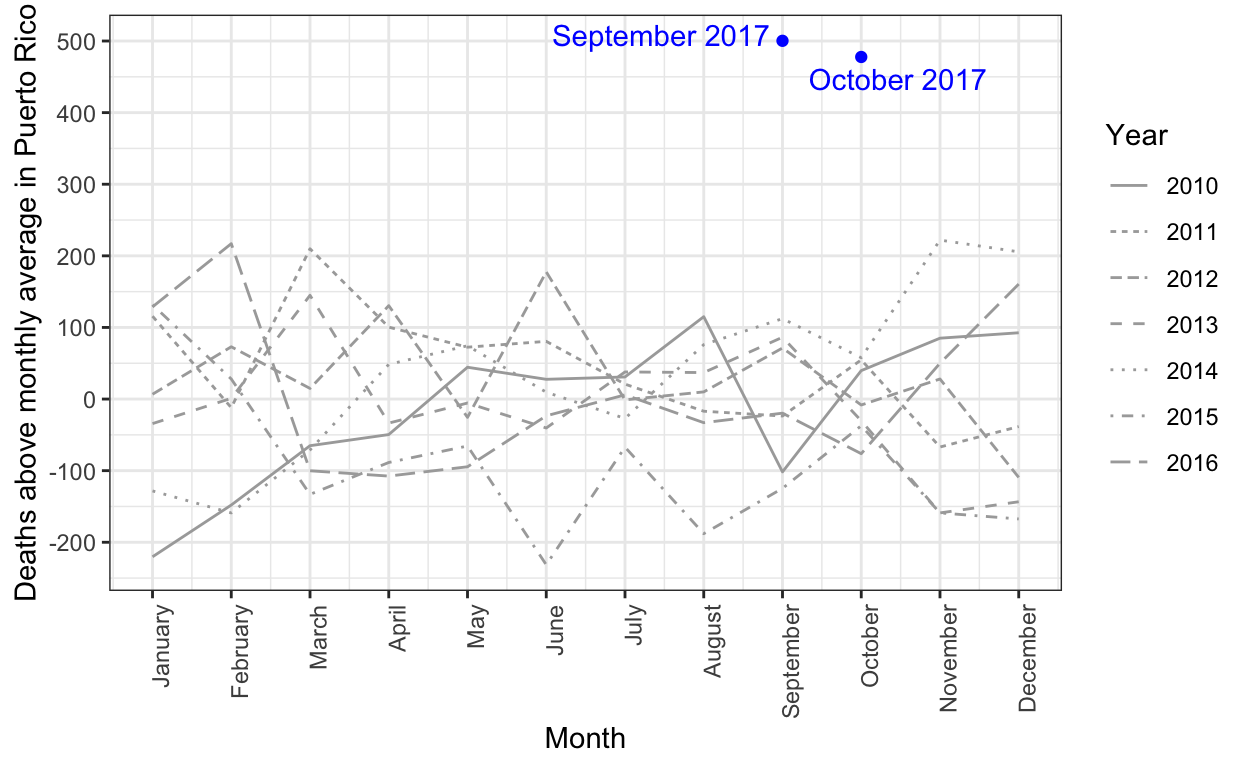

Dec 03 - I scrape the data from PSU study, as described in an earlier post. This data helps guide our study design. Here is a plot of the data that clearly shows that there are more deaths than expected. The plot includes a count for October which is publicized later (see Dec 07 entry).

Dec 05 - We receive data from a Demographic Registry demographer, but it does not include the most important part: the 2017 data. They claim that they “still do not have these data available”.

Dec 05 - We start finalizing the study design for a survey. Based on the limited information we have, we perform a power calculations and decide to make the sample size as large as our funds permit.

Dec 06 - PSU study author replies. But email with data appears to be lost in the mail.

Dec 07 - Centro de Periodismo Investigative (CPI) publishes an estimate of excess deaths based on September and October data of about 1,000. It appears they have 2017 data!

Dec 07 – From this tweet, it appears PSU investigator also has the data. I ask on twitter if CPI or PSU investigator have official data.

Dec 08 – I email PSU investigator asking for data.

Dec 08 - New York Times published a comprehensive article with very nice data visualization and an estimate of 1,052. They have daily data!

Dec 08 – I email first author of New York Times article. She says it took 100 emails/calls to get the data and suggest we contact the Registry director. So now we know the Demographic Registry does in fact have the data.

Dec 08 – It appears that the 2017 data does exist and three different groups were given access. We were told, three days earlier, by the Demographic Registry that they “still do not have these data available”. So I email PRIS again to see if they can help.

Dec 09 – I ask Dr. Buckee to email Registry director to check that it is not just me that is being denied the data.

Dec 11 - PRIS replies. They give us the name of a Registry demographer that gave data to others. PRIS emails Registry directory, again, on our behalf.

Dec 13 – The official death count is about 55 now and Public Security Secretary dismisses current excess deaths estimates. He says this:

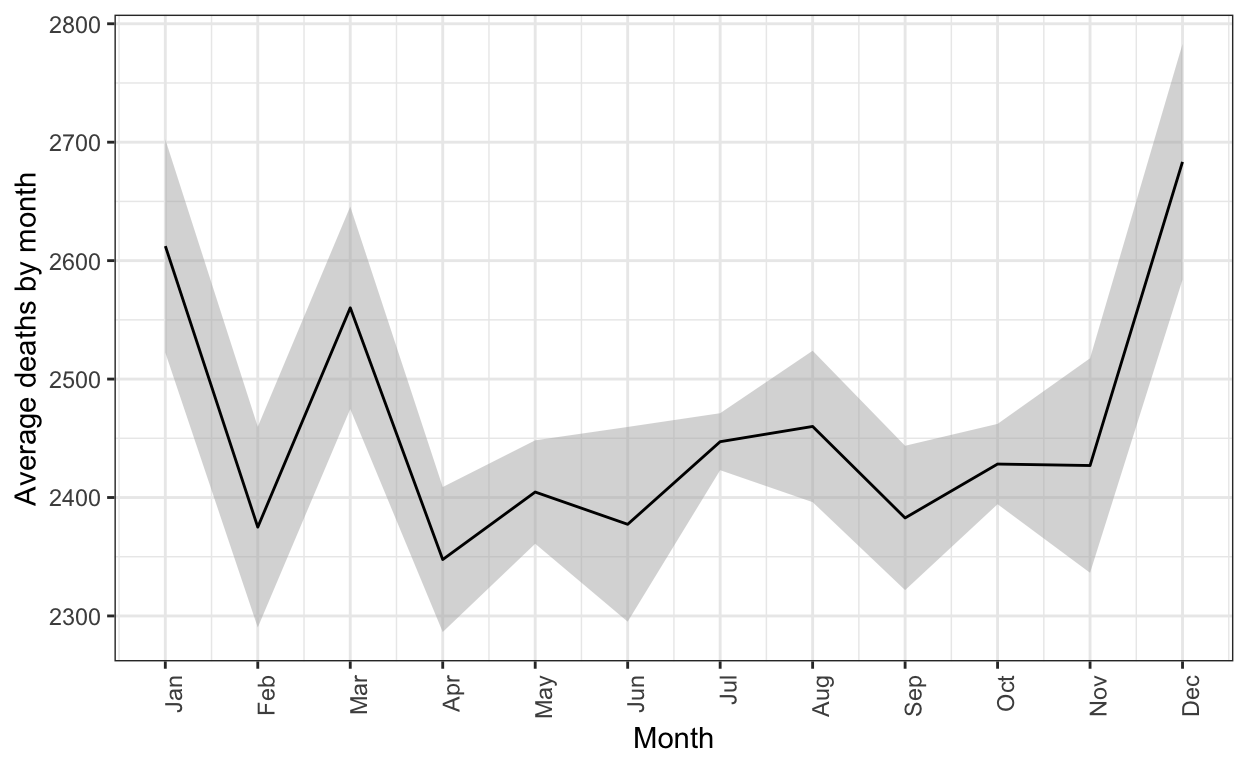

It should be noted that similar numbers are seen in December and January of previous years when no atmospheric phenomenom took place.

Source: https://twitter.com/julito77/status/940945756399243264

This statement shows ignorance of the well-known fact that death rates in the winter are higher than in the fall. You can clearly see this from the Demographic Registry data:

Comment - At this point we become quite concerned. A high ranking government official, who has seen the reports of excess deaths around 1,000 by three different groups, ignores the warnings and instead makes a misguided statement claming what we are observing is normal. It is also concerning that the government is only selectively sharing the data.

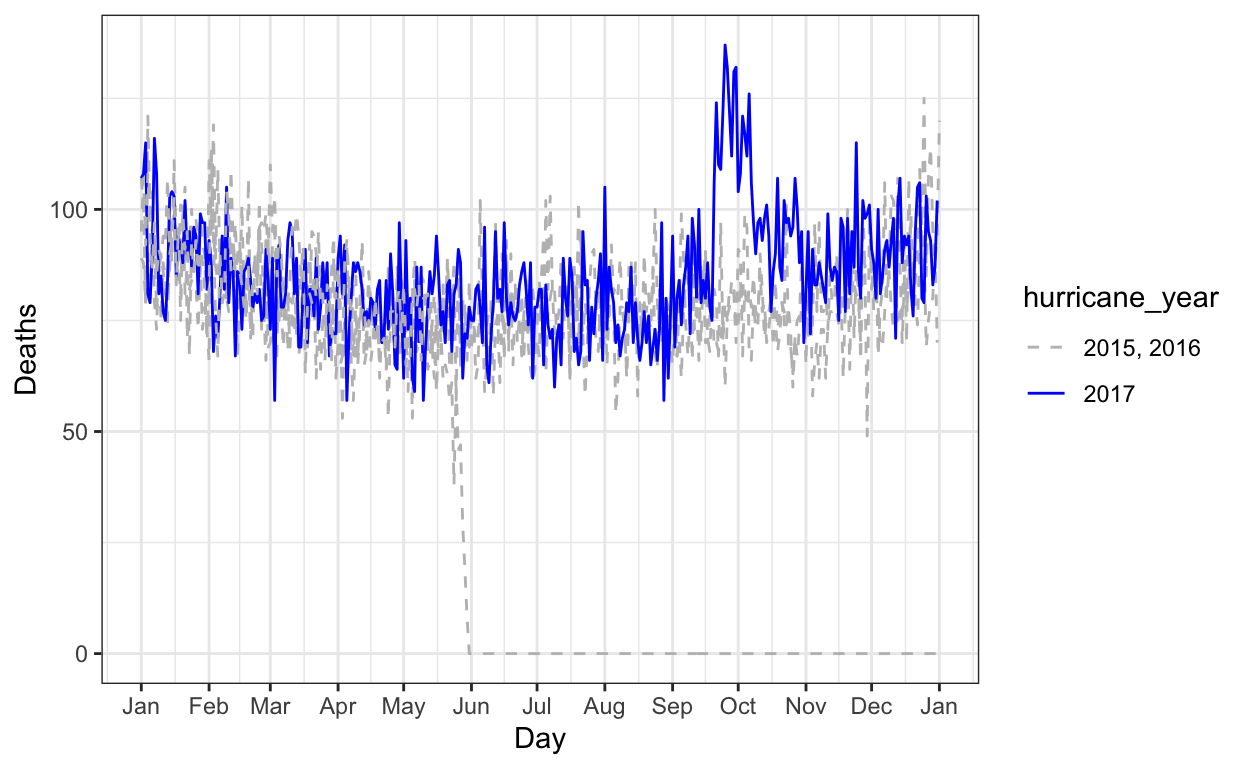

Jan 07 - The New York Times shares the raw data they obtained with us. It’s in PDF! But scrapable. This data shows very clearly that in September and October ther was a huge spike in deaths. However, it is immediately obvious from exploratory data analysis that data for November and December are incomplete:

Jan 16 - Field workers are deployed in Puerto Rico and our survey starts.

Jan 25 - Demographic Registry finally responds to Dr. Buckee saying “we are not authorized to provide new 2017 mortality data.”

Feb 01 - PSU investigator emails Public Security Secretary asking them to make data public.

Feb 22 – Puerto Rico government announces that they have contracted George Washington University (GWU) to perform an independent investigation into the death toll.

Feb 24 - Our household survey is completed. We start analyzing data right away. Our goal is to get the paper published before June 1, the start of hurricane season.

Feb 28 - Latino USA publishes an article showing data provided to them by PRIS. I email PRIS again and they send us data that same day. We immediately see that, like the data we received from New York Times, it appears incomplete:

Mar 16 - First draft of our survey paper is completed and submitted to the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). A particularly troubling finding is the large proportion of deaths attributed to lack of access to medical services. We also see evidence of indirect effects lasting until December 31, the end of the survey period.

May 04 - Survey paper is tentatively accepted by NEJM.

May 25 - Official death count is still at 64. We send a draft of our paper to PR governors office.

May 29 – Our NEJM paper comes out and gets extensive media coverage: 410 outlets including articles in NPR, Washignton Post, New York Times, and CNN. Despite our best efforts, including rewriting our university’s press release, most headlines focus on the point estimate and don’t report uncertainty. All the data and code is made available on GitHub.

May 31 - We post an FAQ (in English and Spanish) explaining the uncertainty in our estimate and making it clear that our study does not say that 4645 (the point estimate) people died.

Jun 01 – PR Governor is interviewed by CNN’s Anderson Cooper who grills him on why the government did not share the data. Governor says data was always available and that there will be “hell to pay if data not available”. That afternoon, PR government makes data public. Dr. Buckee requests the data again. This time we get it almost immediately.

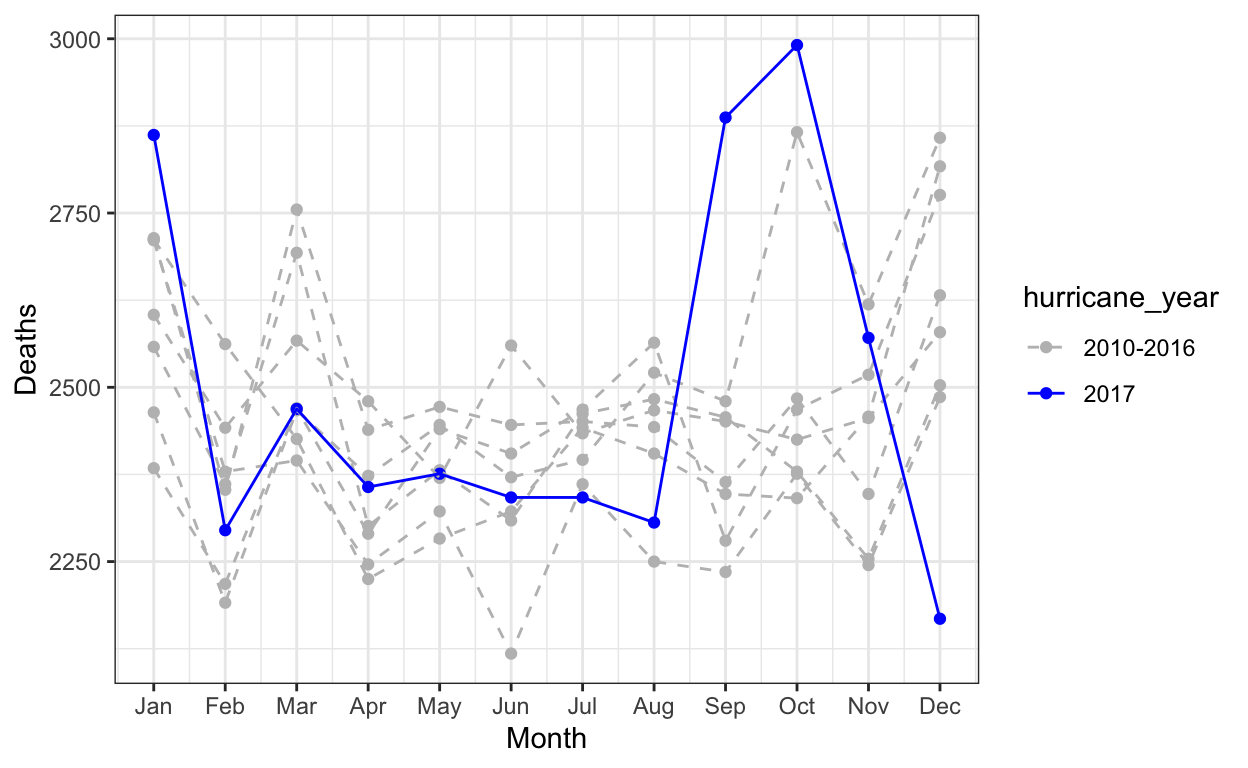

Jun 06 - I post my first analysis with the official mortality data here. The newly released data confirms that the data we were provided earlier were in fact incomplete and that there was a sustained indirect effect lasting past October.

Aug 27 - GWU study comes out with a preliminary estimate of about 3,000 deaths.

Sep 05 - Rolando Acosta and I post a preprint describing an analysis of the newly released data including a comparison to the effects of other hurricanes. We also provide a preliminary estimate of about 3,000 deaths due to indirect effects lasting until April.