When you are doing data science, you are doing research. You want to use data to answer a question, identify a new pattern, improve a current product, or come up with a new product. The common factor underlying each of these tasks is that you want to use the data to answer a question that you haven’t answered before. The most effective process we have come up for getting those answers is the scientific research process. That is why the key word in data science is not data, it is science.

No matter where you are doing data science - in academia, in a non-profit, or in a company - you are doing research. The data is the substrate you use to get the answers you care about. The first step most people take when using data is to collect the data and store it. This is a data engineering problem and is a necessary first step before you can do data science. But the state and quality of the data you have can make a huge amount of difference in how fast and accurately you can get answers. If the data is structured for analysis - if it is research quality - then it makes getting answers dramatically faster.

A common analogy says that data is the new oil. Using this analogy pulling the data from all of the different available sources is like mining and extracting the oil. Putting it in a data lake or warehouse is like storing the crude oil for use in different products. In this analogy research is like getting the cars to go using the oil. Crude oil extracted from the ground can be used for a lot of different products, but to make it really useful for cars you need to refine the oil into gas. Creating research quality data is the way that you refine and structure data to make it conducive to doing science. It means that the data is no longer as general purpose, but it means you can use it much, much more efficiently for the purpose you care about - getting answers to your questions.

Research quality data is data that:

- Is summarized the right amount

- Is formatted to work with the tools you are going to use

- Is easy to manipulate and use

- Is valid and accurately reflects the underlying data collection

- Has potential biases clearly documented.

- Combines all the relevant data types you need to answer questions

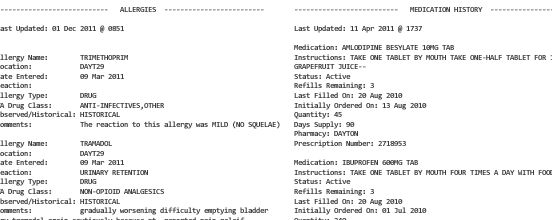

Let’s use an example to make this concrete. Suppose that you want to analyze data from an electronic health record. You want to do this to identify new potential efficiencies, find new therapies, and understand variation in prescribing within your medical system. The data that you have collected is in the form of billing records. They might be stored in a large database for a health system, where each record looks something like this:

_An example electronic health record. Source: http://healthdesignchallenge.com/_

These data are collected incidentally during the health process and are designed for billing, not for research. Often they contain information about what treatments patients received and were billed for, but they might not include information on the health of the patient and whether they had any health complications or relapses they weren’t billed for.

These data are great, but they aren’t research grade. They aren’t summarized in any meaningful way, can’t be manipulated with visualization or machine learning tools, are unwieldy and contain a lot of information we don’t need, are subject to all sorts of strange sampling biases, and aren’t merged with any of the health outcome data you might care about.

So let’s talk about how we would turn this pile of crude data into research quality data.

Turning raw data into research quality data.

Summarizing the data the right amount

To know how to summarize the data we need to know what are the most common types of questions we want to answer and what resolution we need to answer them. A good idea is to summarize things at the finest unit of analysis you think you will need - it is always easier to aggregate than disaggregate at the analysis level. So we might summarize at the patient and visit level. This would give us a data set where everything is indexed by patient and visit. If we want to answer something at a clinic, physician, or hospital level we can always aggregate there.

We also need to choose what to quantify. We might record for each visit the date, prescriptions with standardized codes, tests, and other metrics. Depending on the application we may store the free text of the physician notes as a text string - for potential later processing into specific tokens or words. Or if we already have a system for aggregating physicians notes we could apply it at this stage.

Is formatted to work with the tools you are going to use

Research quality data is organized so the most frequent tasks can be completed quickly and without large amounts of data processing and reformatting. Each data analytic tool has different requirements on the type of data you need to input. For example, many statistical modeling tools use “tidy data” so you might store the summarized data in a single tidy data set or a set of tidy data tables linked by a common set of indicators. Some software (for example in the analysis of human genomic data) require inputs in different formats - say as a set of objects in the R programming language. Others, like software to fit a convolutional neural network to a set of images, might require a set of image files organized in a directory in a particular way along with a metadata file providing information about each set of images. Or we might need to one hot encode categories that need to be classified.

In the case of our EHR data we might store everything in a set of tidy tables that can be used to quickly correlate different measurements. If we are going to integrate imaging, lab reports, and other documents we might store those in different formats to make integration with downstream tools easier.

Is easy to manipulate and use

This seems like it is just a re-hash of formatting the data to work with the tools you care about, but there are some subtle nuances. For example, if you have a huge amount of data (petabyes of images, for example) you might not want to do research on all of those data at once. It will be inefficient and expensive. So you might use sampling to get a smaller data set for your research quality data that is easier to use and manipulate. The data will also be easier to use if they are (a) stored in an easy to access database with security systems well documented, (b) have a data dictionary that makes it clear what the data are and where they come from, or (c) have a clear set of tutorials on how to perform common tasks on the data.

In our EHR example you might include a data dictionary that describes the dates of the data pull, the types of data pulled, the type of processing performed, and pointers to the scripts that pulled the data.

Is valid and accurately reflects the underlying data collection

Data can be invalid for a whole host of reasons. The data could be incorrectly formatted, input with error, could change over time, could be mislabeled, and more. All of these problems can occur on the original data pull or over time. Data can also be out of date as new data becomes available.

The research quality database should include only data that has been checked, validated, cleaned and QA’d so that it reflects the real state of the world. This process is not a one time effort, but an ongoing set of code, scripts, and processes that ensure the data you use for research are as accurate as possible.

In the EHR example there would be a series of data pulls, code to perform checks, and comparisons to additional data sources to validate the values, levels, variables, and other components of the research quality database.

Has potential biases clearly documented

A research quality data set is by definition a derived data set. So there is a danger that problems with the data will be glossed over since it has been processed and easy to use. To avoid this problem, there has to be documentation on where the data came from, what happened to them during processing, and any potential problems with the data.

With our EHR example this could include issues about how patients come into the system, what procedures can be billed (or not), what data was ignored in the research quality database, what are the time periods the data were collected, and more.

Combines all the relevant data types you need to answer questions

One big difference between a research quality data set/database and a raw database or even a general purpose tidy data set, is that it merges all of the relevant data you need to answer specific questions, even if they come from distinct sources. Research quality data pulls together and makes easy to access, all the information you need to answer your questions. This could still be in the form of a relational database - but the databases organization is driven by the research question, rather than driven by other purposes.

For example, EHR data may already be stored in a relational database. But it is stored in a way that makes it easy to understand billing and patient flow in a clinic. To answer a research question you might need to combine the billing data, with patient outcome data, and prescription fulfillment data, all processed and indexed so they are either already merged or can be easily merged.

Why do this?

So why build a research quality data set? It sure seems like a lot of work (and it is!). The reason is that this work will always be done, one way or the other. If you don’t invest in making a research quality data set up front, you will do it as a thousand papercuts over time. Each time you need to answer a new question or try a different model you’ll be slowed down by the friction of identifying, creating, and checking a new cleaned up data set. On the one hand this amortizes the work over the course of many projects. But by doing it piecemeal you also dramatically increase the chance of an error in processing, reduce answer time, slow down the research process, and make the investment for any individual project much higher.

Problem Forward Data Science

If you want help planning or building a research quality data set or database, we can help at Problem Forward Data Science. Get in touch here: https://problemforward.typeform.com/to/L4h89P