Every once in a while, I see a tweet or post that asks whether one should use tool X or software Y in order to “make their data analysis reproducible”. I think this is a reasonable question because, in part, there are so many good tools out there! This is undeniably a good thing and quite a contrast to just 10 years ago when there were comparatively few choices.

The question of toolset though is not a question worth focusing on too much because it’s the wrong question to ask. Of course, you should choose a tool/software package that is reasonably usable by a large percentage of your audience. But the toolset you use will not determine whether your analysis is reproducible in the long-run.

I think of the choice of toolset as kind of like asking “Should I use wood or concrete to build my house?” Regardless of what you choose, once the house is built, it will degrade over time without any deliberate maintenance. Just ask any homeowner! Sure, some materials will degrade slower than others, but the slope is definitely down.

Discussions about tooling around reproducibility often sound a lot like “What material should I use to build my house so that it never degrades*?” Such materials do not exist and similarly, toolsets do not exist to make your analysis permanently reproducible.

I’ve been reading some of the old web sites from Jon Claerbout’s group at Stanford (thanks to the Internet Archive), the home of some of the original writings about reproducible research. At the time (early 90s), the work was distributed on CD-ROMs, which totally makes sense given that CDs could store lots of data, were relatively compact and durable, and could be mailed or given to other people without much concern about compatibility. The internet was not quite a thing yet, but it was clearly on the horizon.

But ask yourself this: If you held one of those CD-ROMs in your hand right now, would you consider that work reproducible? Technically, yes, but I don’t even have a CD-ROM reader in my house, so I couldn’t actually read the data. And a larger problem is that a CD from the 90s probably degraded to the point where it is likely unreadable anyway.

Claerbout’s group obviously knew about the web and were transitioning in that direction, but such a transition costs money. As does keeping a keen eye on emerging trends and technology usage.

Hilary Parker and I recently discussed the how the economics of academic research are not well-suited to support the reproducibility of scientific results. The traditional model is that a research grant pays for the conduct of research over a 3-5 year period, after which the grant is finished and there is no more funding. During (or after) that time, scientific results are published. While the funding can be used to prepare materials (data, software, and code) to make the published findings reproducible at the instant of publication, there is no funding afterwards for dealing with two key tasks:

- Ensuring that the work continues to be reproducible given changes to the software and computing environment (maintenance)

- Fielding questions or inquiries from others interested in reproducing the results or in building upon the published work (support)

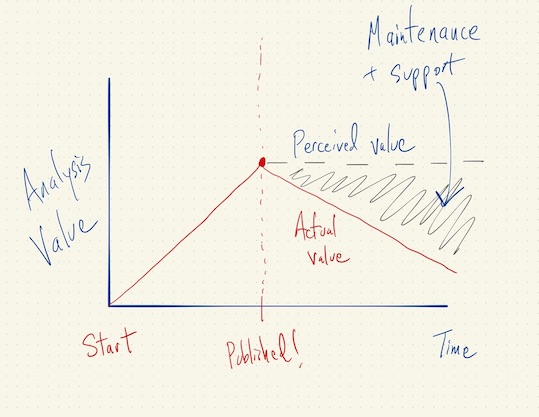

These two activities (maintenance and support) can continue to be necessary in perpetuity for every study that an investigator publishes. The mismatch between how the grant funding system works and the requirements of reproducible research is depicted in the diagram below.

When I say “value” in the drawing above, what I really mean is the “reproducibility value”. In the old model of publishing science, there was no reproducibility value because the work was generally not reproducible in the sense that data and code were available. Hence, this whole discussion would be moot.

Traditional paper publications held their value because the text on the page did not generally degrade much over time and copies could easily be made. Scientists did have to field the occasional question about the results but it was not the same as maintaining access to software and datasets and answering technical questions therein. As a result, the traditional economic model for funding academic research really did match the manner in which research was conducted and then published. Once the results were published, the maintenance and support costs were nominal and did not really need to be paid for explicitly.

Fast forward to today and the economic model has not changed but the “business” of academic research has. Now, every publication has data and code/software attached to it which come with maintenance and support costs that can extend for a substantial period into the future. While any given publication may not require significant maintenance and support, the costs for an investigator’s publications in aggregate can add up very quickly. Even a single paper that turns out to be popular can take up a lot of time and energy.

If you play this movie to the end, it becomes soberingly clear that reproducible research, from an economic stand point, is not really sustainable. To see this, it might help to use an analogy from the business world. Most businesses have capital costs, where they buy large expensive things – machinery, buildings, etc. These things have a long life, but are thought to degrade over time (accountants call it depreciation). As a result, most businesses have “maintenance capital expenditure” costs that they report to show how much money they are investing every quarter to keep their equipment/buildings/etc. up to shape. In this context, the capital expenditure is worth it because every new building or machine that is purchased is designed to ultimately produce more revenue. As long as the revenue generated exceeds the cost of maintenance, the capital costs are worth it (not to oversimplify or anything!).

In academia, each new publications incurs some maintenance and support costs to ensure reproducibility (the “capital expenditure” here) but it’s unclear how much each new publication brings in more “revenue” to offset those costs. Sure, more publications allow one to expand the lab or get more grant funding or hire more students/postdocs, but I wouldn’t say that’s universally true. Some fields are just constrained by how much total funding there is and so the available funding cannot really be increased by “reaching more customers”. Given that the budgets for funding agencies (at least in the U.S.) have barely kept up with inflation and the number of publications increases every year, it seems the goal of making all research reproducible is simply not economically supportable.

I think we have to concede that at any given moment in time, there will always be some fraction of published research for which there is no maintenance or support for reproducibility. Note that this doesn’t mean that people don’t publish their data and code (they should still do that!), it just means they don’t support or maintain it. The only question is which fraction should not be supported or maintained? Most likely, it will be older results where the investigators simply cannot keep up with maintenance and support. However, it might be worth coming up with a more systematic approach to determining which publications need to maintain their reproducibility and which don’t.

For example, it might be more important to maintain the reproducibility of results from huge studies that cannot be easily replicated independently. However, for a small study conducted a decade ago that has subsequently been replicated many times, we can probably let that one go. But this isn’t the only approach. We might want to preserve the reproducibility of studies that collect unique datasets that are difficult to re-collect. Or we might want to consider term-limits on reproducibility, so an investigator commits to maintaining and supporting the reproducibility of a finding for say, 5 years, after which either the maintenance and support is dropped or longer-term funding is obtained. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the data and code suddenly disappear from the world; it just means the investigator is no longer committed to supporting the effort.

Reproducibility of scientific research is of critical importance, perhaps now more than ever. However, we need to think harder about how we can support it in both the short- and long-term. Just assuming that the maintenance and support costs of reproducibility for every study are merely nominal is not realistic and simply leads to investigators not supporting reproducibility as a default.